My Top Summer Reads: A Bit of Scandinavian, Hungarian, Japanese Literatures & More - 2023

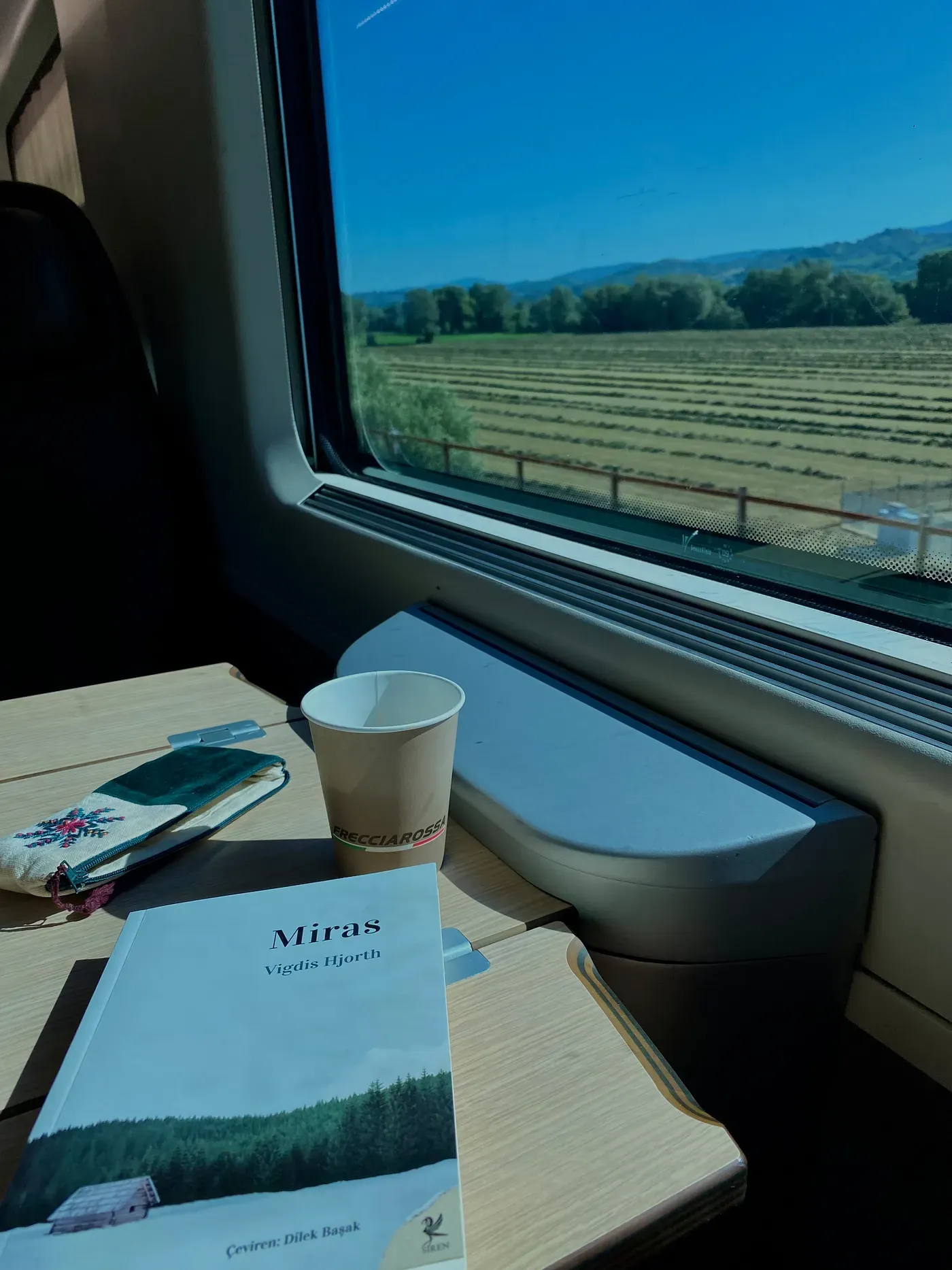

Books that kept me company some summers ago.

What can I say? I love reading. Diving into different stories has always held a strong allure for me. To be honest, life is too short to explore different experiences, embrace a range of emotions, and meet a diverse array of people. So there is nothing to do but reading! Unfortunately, this summer, I had prior commitments that limited my reading time. However, I consider myself fortunate to have discovered six remarkable stories by six talented authors. Here are the eight books; everyone should give six of them a chance:

First and foremost, I’d like to begin with a disclaimer. While I read some of these books in English and others in Turkish translated versions, a few of my comments were initially made in Turkish. I will now endeavor to provide accurate translations with the appropriate sentiment.

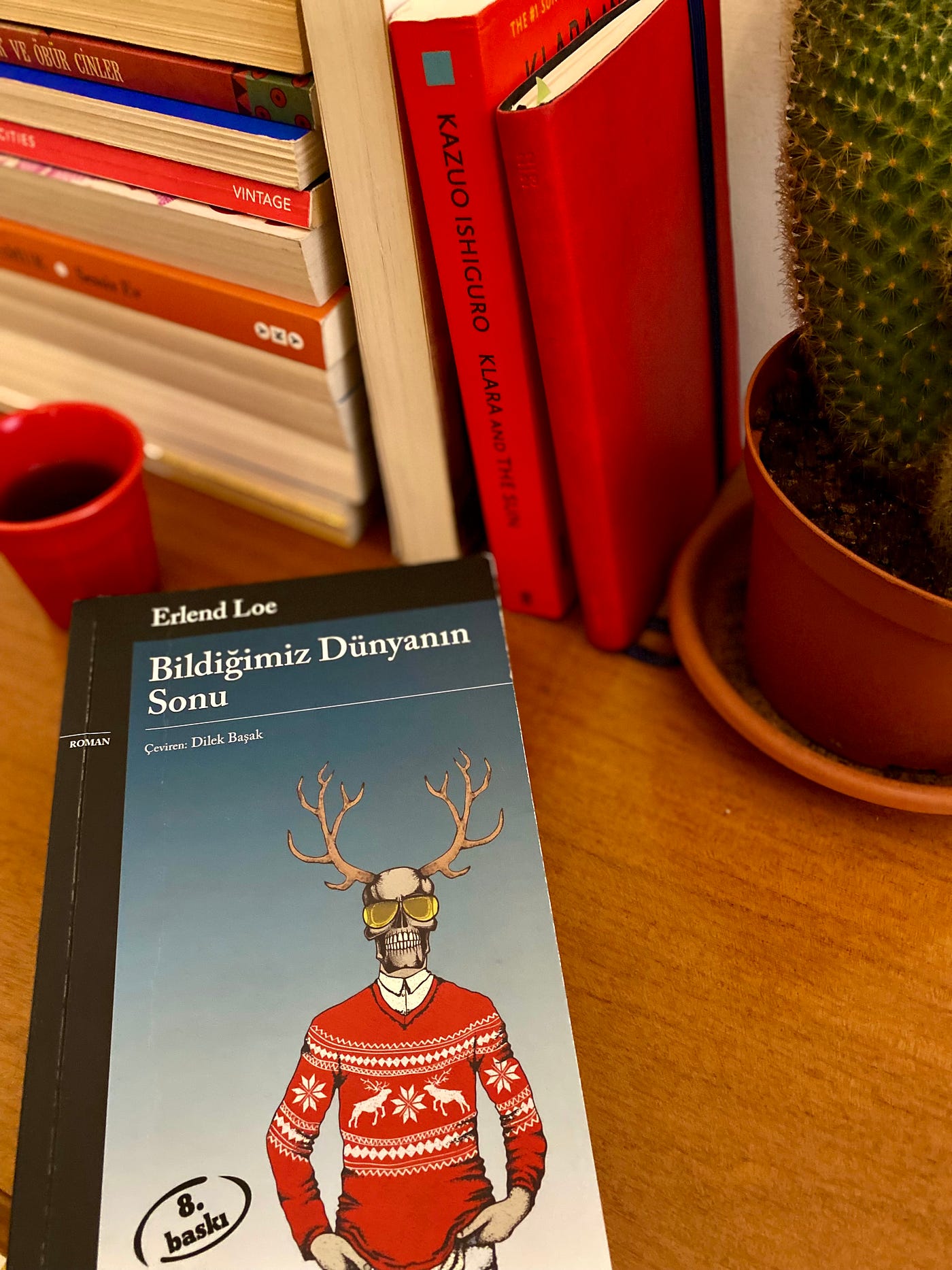

1. “Slutten på verden slik vi kjenner den” (The End of the World as We Know It) by Erlend Loe

Andreas Doppler… What can I say? After 3 books, I can admit that I like him, but only as a third eye watching from the outside. If my husband did such a crazy thing and moved to the forest, left the country, came back and did such weird things, whether it was burning things in the house, masturbating all over the house and ruining the house, I would probably call the police. Unlike the first 2 books, in the last book, Doppler’s point about overconsumption and the “oversharing” habits that come with it, which is unfortunately something I have done and then questioned in our society — to say on behalf of myself — and the fact that it has become an addiction to put it more accurately, is discussed in more detail. As an academic candidate who is trying to specialise in the field of online consumer behaviour, I found many thought-provoking elements in the book, which made me enjoy the book as someone who loves the series (Doppler), as it is a subject that I have already questioned, questioned myself and criticised a lot. The only thing I didn’t like, and this is a big cultural thing, is that Doppler follows a woman because he likes her physique and after 5–10 minutes, he regrets it and sincerely apologises to the woman with a statement like “I objectified your ass, I’m sorry” and the woman thanks him very calmly and advises Doppler to work on this problem. Is everyone in Scandinavian countries so cool and calm? Too calm moments in this style reduced the realism of the book for me, but how much of a problem is exaggeration where there is already satire? Let’s say my Mediterranean genetics had difficulty understanding the Scandinavian calmness ☺. Another thing that haunts me is why nobody took this guy to a specialist like a neurologist or a psychiatrist. It is very clear that his brain was not very healthy after the head trauma and the death of his father. While this thought was in my mind from the very beginning, the part where his family threw him out of the door and he stayed on the street (slightly inspired by the story of The Little Match Girl) shattered my heart, but the fact that Doppler was somehow happy without revealing the ending repaired my broken heart a little.

2. “Everyone You Hate is Going to Die” by Daniel Sloss

A marvellous book that I made more strange noises to hold my laughter while reading in public. I think I haven’t read or even watched something I laughed so much for a long time, and I have to admit that I regularly harass people in my close circle to make them read this particular, but read it please. Make everyone read it. Thank you. Daniel Sloss, who is successful in his field both as a comedian and as a “writer”, brings the twisted and abnormal aspects of all kinds of relationships in our lives to the reader in a funny way, but what I realised in this book and what everyone should realise is that there are too many people who think “am I abnormal?” and the dynamics we see as abnormal are very, very normal.

It is a book that I would like to talk about each chapter for hours if I could. It is a very easy to read, very fun and enjoyable book. Please read it!

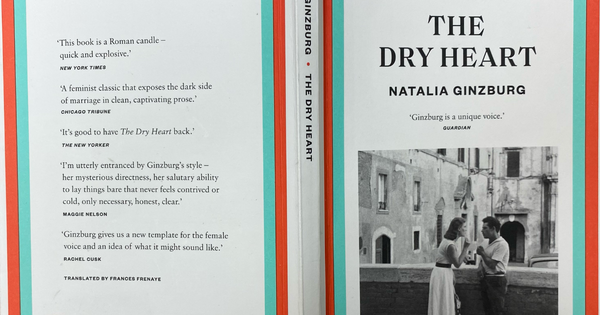

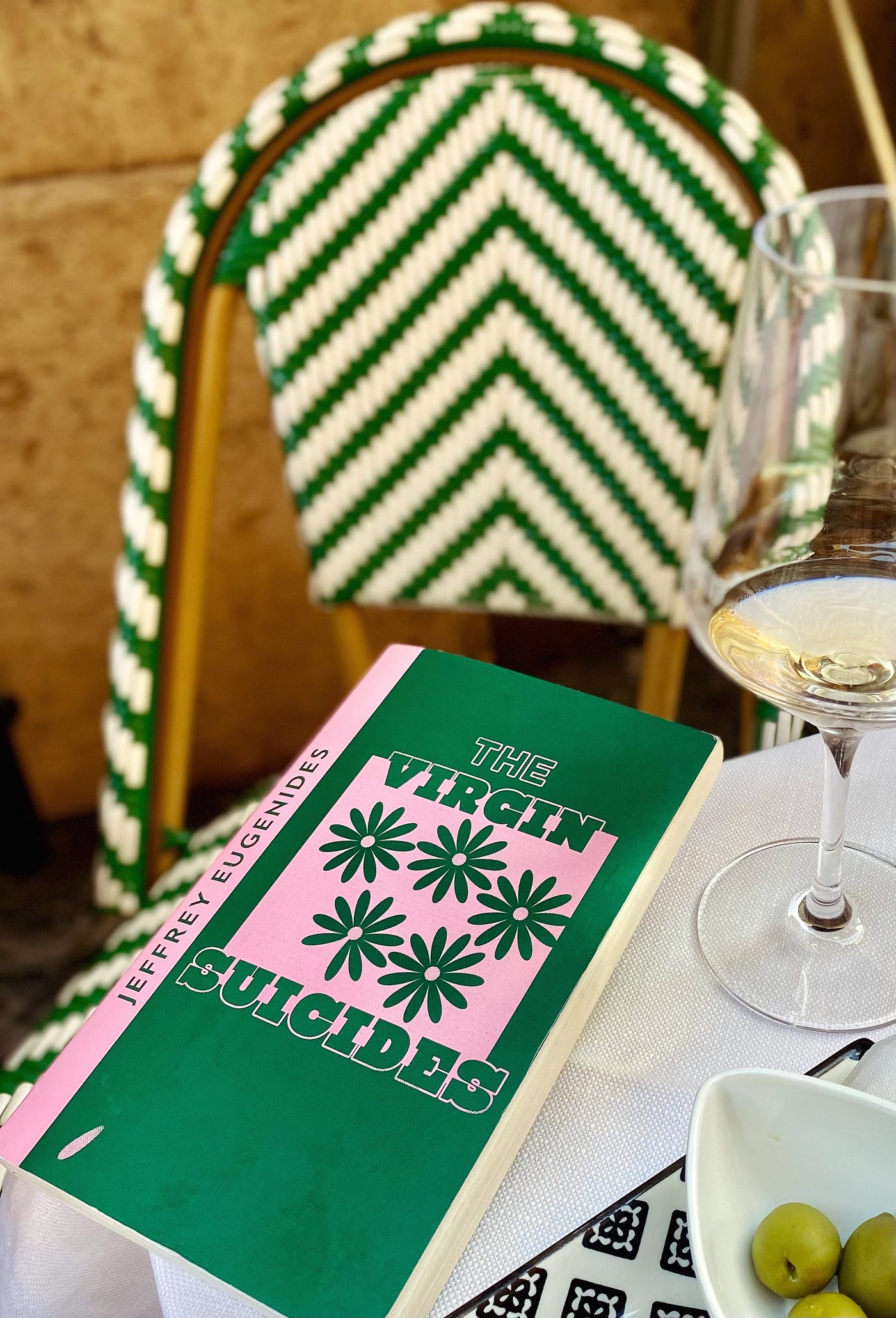

3. “The Virgin Suicides” by Jeffrey Eugenides

I took notes while reading the book so that I would definitely mention them, but I was so overwhelmed in the last 70–80 pages. I don’t understand how it got so many good reviews and high scores on so many platforms. The story starts really well — in terms of literature and gripping. After all, a story about the suicide of 5 sisters would not be beautiful. But then the unnecessary descriptions on the following pages and in fact, I think the author wanted to try something different in literary terms, but in doing so, the main character and the events remained superficial, so it could not go beyond a boring work for me. On the pages where I still had hopes for the book, I wrote the following:

“There are certain movements that stayed in my mind after my great (!) high school literature performance, and this book is a loud symbolism for me, but we also see postmodern influences in many parts. A novel set in 1970s America would be considered postmodern, but there are so many symbols emphasised throughout the story. For example, Cecilia’s wedding dress that sticks to her, the Virgin Mary photo, which is a symbol mentioned from the first pages, etc.”

And I was seriously behind these thoughts, but after a point, I could not understand who “we” was telling the story, the suicide of 4 sisters happened in 3 pages and it was over. The back cover already gave us that it was the situation at home that made those girls that way, so there was no need to read the book.

4. “Before Your Memory Fades” by Toshikazu Kawaguchi

Before Your Memory Fades, the 3rd book of this “sweet” series, which started with Before the Coffee Gets Cold, and which I thought would have remained as a trilogy, is not very different from the first 2 books when we look at the stories. It is a really sweet book that is easy to read and pushes you to make some inner judgement. As you know, Toshikazu Kawaguchi has written a clean book without using unnecessary dramatic elements without using cryptic sentences, without using long descriptions, in a clear language, this time in a different cafe, but keeping our main characters constant and making small additions to them to multiply the stories.

As a criticism for this book, we have been in the same line for 3 books now and it could have gone a little deeper from the perspective of Kazu and Nagare rather than others, at least as a passionate reader I would have liked to see this.

But the money will be sweet that our author published the 4th book this year. What can I say, good luck. I will probably give it a go because I have learn the ending, if there is one.

Those who want to spend some time and read simple stories should definitely read it.

5. “A Room of One’s Own” by Virginia Woolf

This book lifted me up and made me feel incredibly empowered, which is why i am just sharing the mini review I wrote in the heat of the moment:

Such a beautiful day to destroy patriarchy. 🤞🏼💕 After watching and LOVING Barbie the movie — yes, judge me if you must, but hear me out — my understanding of gender dynamics has evolved in unexpected ways. Moreover, reading “A Room of One’s Own” by the remarkable Virginia Woolf has been an enlightening experience. I’m humbled to have discovered this literary treasure after 29 years on this planet. This timeless masterpiece is a must-read for all, shedding light on the enduring struggle against historic inequalities. Woolf’s poetic prose brilliantly captures the essence of our collective journey. Each sentence feels like a treasure worth cherishing. Every girl, woman, nonna & donna must read this masterpiece.

6. “Judit… és az utóhang” (Portraits of a Marriage) by Sandor Marai

An incredible masterpiece. I don’t know why and how I didn’t meet one of the most talented writers of Hungarian literature until this book.

“As the bourgeois world of Central Europe quietly collapses, two women and a man are tested by loneliness in the sharp corners of a story wrapped in passion, longing and impermanence: Is true love always fatal?”

So, is the story told in this book really love, or is it that Peter and Judit are supposedly bound to each other because they cannot take revenge on the system they are in?

In fact, in most reviews it is written that we hear about love, betrayal and revenge from 3 different people, which technically it is, and we read a period of 20 years from the eyes of Ilonka, then Peter and Judit. It is definitely not a simple love story, the author has told the bourgeoisie of the period from different parts of the system in such a way that you cannot put the book down. In all 3 chapters, while there is a single person narration, the inner reckoning of the characters is described in an incredible language, and it is a psychologically very finely processed work. He analysed emotions and motives to the finest detail, so much so that I kept asking myself: How can one person have so much knowledge about human nature? If I could, I would share the whole book here.

In this story, Peter and Judit are supposedly great lovers, but it is a fascinating adventure as it unfolds in front of you layer by layer as you read to understand why both sides psychologically immerse themselves in this relationship. Peter has never received that love from his family, and in his 30s, he has been living with his family and there is the “peasant girl” working for them, and yes, he supposedly fell in love with her. But I think it was a silent rebellion, sort of complaining that his first wife was petty bourgeois and then thinking that he was in love with someone from a lower class. He also constantly complained about arrogance and ego, and every action he took was motivated by arrogance and ego. The same thing is very dosed and beautifully handled when Judit talks about all the bourgeoisie traditions and customs with disgust 3 lines after declaring that she does not disparage the rich. Judit is a perfect example of the fact that even if you take a person out of the slum, you cannot take the slum out of him/her. I cannot understand how the poverty of one’s past can legitimise the destruction of other people’s lives in order to take revenge on the system. I think this is just being mean spirited. Nothing that the woman went through is normal, and it is very sad, but to wait for the gentleman of the house when she realises his interest and to bring herself to his mind while married with cheap tricks is just plain simplicity in my eyes.

I don’t want to reveal anything more — after writing the whole story — it should definitely be read. A marvellous work.

7. “Bu Hikaye Senden Uzun Osman” by Aylin Balboa

This book is written in Turkish and I hope there is no translation in any other language, if there is, I have no opinion about it:

I want a refund, Osman! I think it’s one of the worst books I’ve read recently.

1. This is not a book written in the story genre, it is impossible to understand why it is defined as a story.

2. The way she tried to explain her own feelings in every paragraph with constant analogies and links like “there is something like this” was incredibly boring.

3. In general, I can say that I silently prayed for it to end while reading because her language and style were very far from my literary taste.

4. If the author had shared what she wrote here on Twitter instead of the book, there wouldn’t have been such a waste of paper…

You’ve killed me, Osman.

8. Arv og Miljø (Will and Testament) by Vigdis Hjorth

I feel like I have just come out of long hours and days of therapy. It is an incredible work.

At the beginning of this book, which is not about huts, but about the traumas inherited from one’s childhood in a simple yet striking way, it seems like a simple inheritance issue and the family dynamics related to it. In fact, as a Turkish citizen, I have to admit that I thought, “What trauma can these Scandinavians have?”.

But as it progresses, the question “I wonder?” starts to probe a little bit and bam! We are faced with that horrible truth and a lot of horrible derivatives such as the family’s reaction / lack of reaction etc…

One of my favourite features of Scandinavian literature is that rather than lyrical and dramatic narration, it simply, clearly but with the same power mobilises all the reader’s empathy senses, and this book is one of its best examples.

Vigdis Hjorth wrote an incredible work.